Aug 19, 2017 - 4 minutes

♞ What Chess Teaches Us about Effective Presentations

A few years ago, I was giving a talk at work on “fun presentations”, as part of an inter-departmental information sharing program. In a corporate environment, fun can be rare, and some of us took every opportunity we could to inject more of it in our work.

At the time, I was new to chess (sort of), and while preparing for one of the above sessions, it dawned on me that I could incorporate chess principles into my talk, to make it more memorable. Below is a summary of that.

What’s Chess?

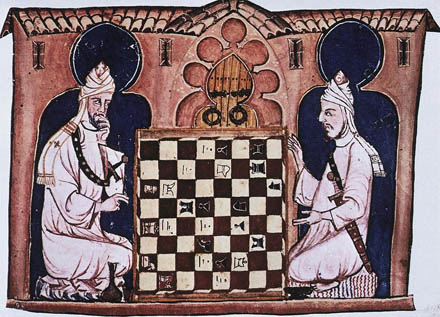

Chess is a fascinating board game of strategy and resilience, the origins of which are unclear. Some claim it originated in Persia in the form of Shatranj; others say it was Ancient Egypt, in what might’ve been an early version of the game, called Senet. Some say it was born in China, referring to the game Liubo. Evidence, however, suggests that India was its birthplace, where it was known as Chaturanga. One thing is for sure—it’s at least 1500 years old.

There are more possible games of chess than there are atoms in the universe. In fact, after only the fifth move, the game can unfold in about five million different ways. If that doesn’t blow you away, I’m not sure what will!

Principles

In chess, the objective of the game is to win—ideally by checkmate (‘capturing’ the enemy ♚King.) It’s important in a presentation, as it is in chess, to know one’s objective before doing anything else. What is it that you wish to achieve?

1. The Opening

Openings are important, because they set the context for everything else that happens next. It tells your opponent, or in this case your audience, what to expect. This may sound like common sense, but it’s surprising how we often neglect working on our opening lines.

One of the opening principles in chess is to control the center. A move such as the one in the following image would be considered weak; irrelevant to the game. No one will take you seriously. “You’re not playing in the center”, they would say, and not addressing the core of what you’re going to talk about.

An opening should be:

- Powerful: Grasping, and even demanding, attention

- Relevant to the rest of your presentation

A good opening is not, of course, made up of a single move or sentence. It’s a sequence of moves or things you say that build up to a good, relevant story—something that paints a clear picture for your audience.

2. Knowing your Opponent/Audience

“Play the person, not the position” is a common saying in chess, where one player attempts to use to their advantage the psychology of their opponent. For a successful presentation, it’s vital to know who you’re going up against. Who are your stakeholders? Know them, what they want, what makes them tick, and what doesn’t. This will help you address what they care about, and anticipate questions or concerns they might raise.

Garry Kasparov (shown above), who was the world’s number one player for 20 consecutive years, studied and prepared for his opponents diligently. You should, too.

3. Preparation and Practice

In chess, there’s a lot of theory. No matter how well you know it, you’re useless on the board if you’ve not actually played, and practiced. So, here’s my advice to you:

- Grab a friend (or a chimp), and rehearse your presentation with them.

- Think about what possible moves your opponent might make, or questions they might ask, and how you would respond to them.

- Practice your time. If you have five minutes to present, make sure you deliver in five minutes. If you have fifty, adjust your content in accordance, and make it engaging.

Last words

I hope you found the above useful, and if you haven’t, at least you’ve learned something new about chess!

And remember—in life, as in this ancient game, failure and defeat are inevitable. Don’t give up.

Hi there! 👋 Want to be informed of new posts via email?