Oct 01, 2019 - 10 minutes

📖 Becoming by Michelle Obama

Rating: 🌕🌕🌕🌕🌗

Even if we didn’t know the context, we were instructed to remember that context existed. Everyone on earth, they’d tell us, was carrying around an unseen history, and that alone deserved some tolerance.

I wouldn’t have picked up this book were it not for the recommendation of a friendly stranger whom I got to know over a cup of coffee in a cozy café in Ho Chi Minh City, a little less than a year ago. I never met her again, but the way she spoke of Michelle Obama stuck with me for days to come. Who is this “Michelle”, I thought, and what made her so godlike in the eyes of my brief afternoon companion?

It’s easy to dismiss political figures as other-wordly beings, entities that are not quite human; cold, arrogant, rich, full of power and devoid of emotions or a sense of how it’s like to be a commoner. It’s even easier to dismiss the spouses of political figures. I’ve always had a fondness for the Obamas, but to me, at the end of the day, they were politicians—Barack was the president, and Michelle the first lady. Extraordinary people, for sure, but politicians, still.

Becoming was, therefore, a big, heartwarming slap in the face for me. Nothing I knew or assumed about Michelle and her husband was true. I was delighted, for instance, to learn in the first quarter of the book that Michelle was Barack Obama’s mentor at a law firm (that is how they first met), and that he showed up late on his first day.

I was surprised to find out that Michelle was an active participant in Obama’s election campaigns. While he was giving a speech in one city, she was giving one in another. He had a team of organizers, and so did she. It was almost as if they were running for president as a team, rather than an individual. Their partnership is one to admire.

Being the first lady of the United States doesn’t exactly come with a job description, and it was up to, well, the first lady, to do whatever she wanted to do, and to shape that role in whichever way she deemed fit. In the book, Michelle details the different initiatives she established, why she established them, and the impact those programs have had since. She speaks in depth about the people she worked with, and how they often turned from coworkers to lifelong friends.

Perhaps my favorite parts of the book, however, are where she talks about her childhood, her personal relationships, her dreams and insecurities, her teenage years, and her family. The way she describes her relationship with Barack is both admirable and hilarious. Through those paragraphs is where it becomes clear that she, and many other public figures out there are, in fact, human. She didn’t come from a privileged background. Both Michelle and Barack had a “conventional”, if not difficult, upbringing. She had regular teenage thoughts, and cared about regular teenage things. Coming to think of it, why wouldn’t she? She’s an ordinary, hardworking member of common society who happened to get involved with someone who ended up becoming the president of the United States.

Overall, this was an enlightening read for me. I hope that you, kind reader, will understand that this is not a review of American politics, or of the Obama administration’s policies. This is a review of a book written by a one Michelle Robinson, a person we can all look up to in some way or another, regardless of our political beliefs.

As usual, some tidbits from the book (possibly containing spoilers):

I’ve heard about the swampy parts of the internet that question everything about me, right down to whether I’m a woman or a man.

Even if we didn’t know the context, we were instructed to remember that context existed. Everyone on earth, they’d tell us, was carrying around an unseen history, and that alone deserved some tolerance.

Failure is a feeling long before it becomes an actual result. It’s vulnerability that breeds with self-doubt and then is escalated, often deliberately, by fear.

Being around boys, I was slowly coming to realize, was fun. […] Because what was a basketball game if not a showcase of boys? I’d wear my snuggest jeans and lay on some extra bracelets and sometimes bring one of the Gore sisters along to boost my visibility in the stands. And then I’d enjoy every minute of the sweaty spectacle before me—the leaping and charging, the rippling and roaring, the pulse of maleness and all its mysteries on full display.

But my first months at Whitney Young gave me a glimpse of something that had previously been invisible—the apparatus of privilege and connection, what seemed like a network of half-hidden ladders and guide ropes that lay suspended overhead, ready to connect some but not all of us to the sky.

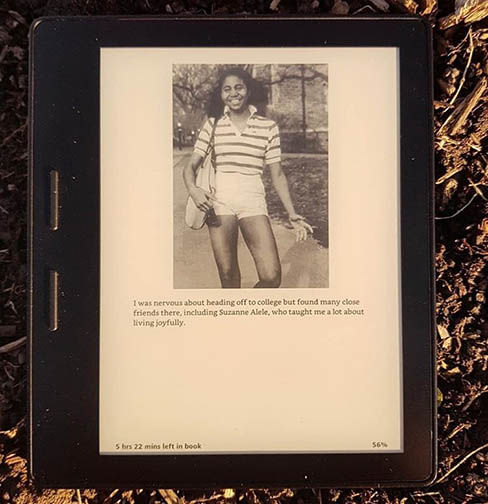

I see now that she provoked me in a good way, introducing me to the idea that not everyone needs to have their file folders labeled and alphabetized, or even to have files at all. Years later, I’d fall in love with a guy who, like Suzanne, stored his belongings in heaps and felt no compunction, really ever, to fold his clothes. […] I am still coexisting with that guy to this day. This is what a control freak learns inside the compressed otherworld of college, maybe above all else: There are simply other ways of being.

He [Barack Obama] was refreshing, unconventional, and weirdly elegant. Not once, though, did I think about him as someone I’d want to date. For one thing, I was his mentor at the firm. I’d also recently sworn off dating altogether, too consumed with work to put any effort into it. And finally, appallingly, at the end of lunch Barack lit a cigarette, which would have been enough to snuff any interest, if I’d had any to begin with. He would be, I thought to myself, a good summer mentee.

I’d been Mrs. Obama for the last twelve years, but it was starting to mean something different. At least in some spheres, I was now Mrs. Obama in a way that could feel diminishing, a missus defined by her mister. I was the wife of Barack Obama, the political rock star, the only black person in the Senate—the man who’d spoken of hope and tolerance so poignantly and forcefully that he now had a hornet buzz of expectation following him.

“You’ve become a force in the campaign, which means people are going to come after you a little. This is just the nature of things.”

I was female, black, and strong, which to certain people, maintaining a certain mind-set, translated only to “angry.” It was another damaging cliché, one that’s been forever used to sweep minority women to the perimeter of every room, an unconscious signal not to listen to what we’ve got to say.

Regardless of what I chose to do, I knew I was bound to disappoint someone. The campaign had taught me that my every move and facial expression would be read a dozen different ways. I was either hard-driving and angry or, with my garden and messages about healthy eating, I was a disappointment to feminists, lacking a certain stridency.

It seemed that my clothes mattered more to people than anything I had to say. In London, I’d stepped offstage after having been moved to tears while speaking to the girls at the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson School, only to learn that the first question directed to one of my staffers by a reporter covering the event had been “Who made her dress?”

One of them then gave me a candid look. “It’s nice that you’re here and all,” he said with a shrug. “But what’re you actually going to do about any of this?”

I’m an ordinary person who found herself on an extraordinary journey. In sharing my story, I hope to help create space for other stories and other voices, to widen the pathway for who belongs and why.

And a few longer bits:

If you wanted to work as an electrician (or as a steelworker, carpenter, or plumber, for that matter) on any of the big job sites in Chicago, you needed a union card. And if you were black, the overwhelming odds were that you weren’t going to get one. This particular form of discrimination altered the destinies of generations of African Americans, including many of the men in my family, limiting their income, their opportunity, and, eventually, their aspirations. As a carpenter, Southside wasn’t allowed to work for the larger construction firms that offered steady pay on long-term projects, given that he couldn’t join a labor union.

Like any newish couple, we were learning how to fight. We didn’t fight often, and when we did, it was typically over petty things, a string of pent-up aggravations that surfaced usually when one or both of us got overly fatigued or stressed. But we did fight. And for better or worse, I tend to yell when I’m angry. When something sets me off, the feeling can be intensely physical, a kind of fireball running up my spine and exploding with such force that I sometimes later don’t remember what I said in the moment. Barack, meanwhile, tends to remain cool and rational, his words coming in an eloquent (and therefore irritating) cascade. It’s taken us time—years—to understand that this is just how each of us is built, that we are each the sum total of our respective genetic codes as well as everything installed in us by our parents and their parents before them. Over time, we have figured out how to express and overcome our irritations and occasional rage. When we fight now, it’s far less dramatic, often more efficient, and always with our love for each other, no matter how strained, still in sight.

I didn’t think it was a great idea for Barack to run for office. My specific reasoning might have varied slightly each time the question came back around, but my larger stance would hold, like a sequoia rooted in the ground, though clearly you can see that it stopped absolutely nothing. In the case of the Illinois senate in 1996, my reasoning went like this: I didn’t much appreciate politicians and therefore didn’t relish the idea of my husband becoming one. Most of what I knew about state politics came from what I read in the newspaper, and none of it seemed especially good or productive. My friendship with Santita Jackson had given me a sense that politicians were often required to be away from home. In general, I thought of lawmakers almost like armored tortoises, leather-skinned, slow moving, thick with self-interest. Barack was too earnest, too full of valiant plans, in my opinion, to abide by the hardscrabble, drag-it-out rancor that went on inside the domed capitol downstate in Springfield. In my heart, I just believed there were better ways for a good person to have an impact. Quite honestly, I thought he’d get eaten alive.

The last bit of work he did, usually at some hour past midnight, was to read letters from American citizens. Since the start of his presidency, Barack had asked his correspondence staff to include ten letters or messages from constituents inside his briefing book, selected from the roughly fifteen thousand letters and emails that poured in daily. He read each one carefully, jotting responses in the margins so that a staffer could prepare a reply or forward a concern on to a cabinet secretary. He read letters from soldiers. From prison inmates. From cancer patients struggling to pay health-care premiums and from people who’d lost their homes to foreclosure. From gay people who hoped to be able to legally marry and from Republicans who felt he was ruining the country. From moms, grandfathers, and young children. He read letters from people who appreciated what he did and from others who wanted to let him know he was an idiot.

Hi there! 👋 Want to be informed of new posts via email?