Sep 27, 2021 - 8 minutes

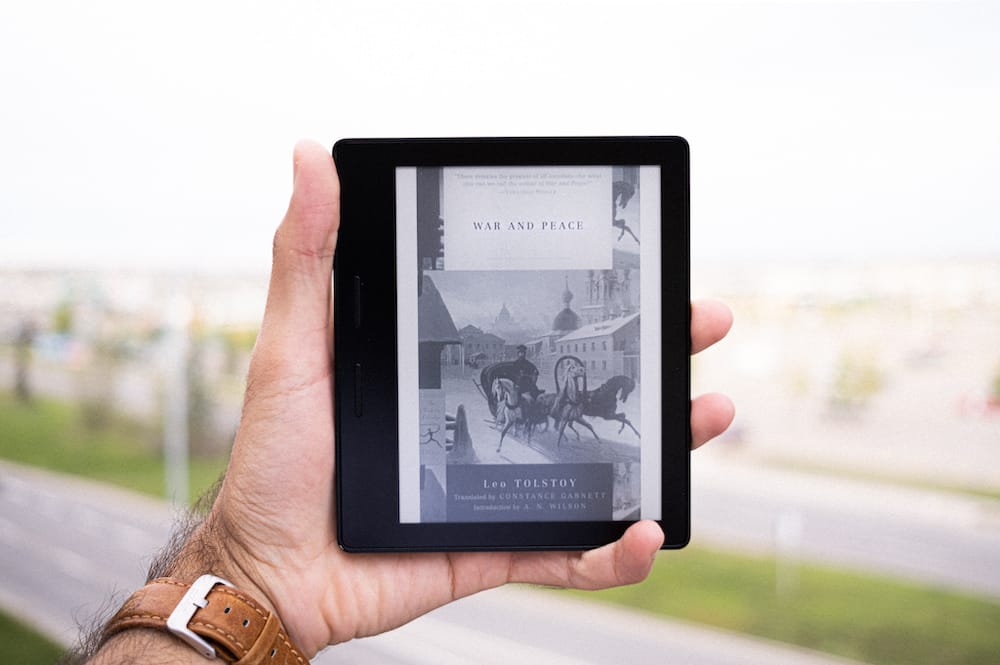

📖 War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy

Rating: 🌕🌕🌕🌕🌑

Eleven years ago I was momentarily consumed—as a young man gets when life isn’t actively kicking him in the groin—with impressing a love interest. My obsession led me to my first copy of War and Peace, a scary-looking $3 paperback that had somehow managed to squash Tolstoy’s monster down to the size of a fist. A big fist. The book sat untouched for years, establishing its place as the prime member of the resident book club “Honorary Furniture”. My then lover was not impressed. War and Peace has haunted my nights since, and so has, occasionally, my dear one.

And here we are. I read it. And I am impressed. Is it the greatest novel ever written? Yes, but only if by ‘great’ you mean ‘big’. So, no, it is not. I hesitate in writing this review because I worry that, owing to my complete lack of qualifications for the job, I may not be able to do the book justice. I wouldn’t be the first idiot to publish something on the internet, though, so I’m deciding not to care. You should also know that Tolstoy disliked the term ‘novel’, saying that War and Peace “is not a novel, and even less is it a poem”.

Let us return to my dearly departed, who may or may not be fictional. I informed her of my recent accomplishment, but “I finished that book from when we were” turned out to be a poor conversation starter. She said “cool” (quietly, and in her head), and that was that. I have an urge to tell you about how she was War and how she was Peace, and that without reading the book I have intimate knowledge of the meaning of these two opposites, but I’m not going to. Those thoughts are mine, and mine alone.

Now that I have shared some of my misery with you, let me tell you about this book. If you’re expecting a synopsis, please forgive me for dragging you this far—you may need to look elsewhere. I’m only here to tell you about the hilarity of Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy, who one day decided to sit down and write a 1500 page novel on the most boring subject in the universe: Peace. Everything was quiet, and his pages empty, until War came along and did its war-y thing. This book, to me, is a laugh in the face (disguised as a novel) of every single human military enterprise. It makes a mockery of the entire affair, and presents with utmost clarity the stupid fragility of the rich and powerful. Historians were not spared, either. Tolstoy drags them through the mud and ridicules the whole business with a sense of humor that I’ve grown fond of.

Imagine with me for a minute the following scenario — You are an infantry soldier marching towards destination X in 1812, without the convenience of GPS, airplanes, or text messaging. You arrive at what really is a best-guess; you have no way of knowing that it’s where you need to be, and neither do the other infantries. Something unexpected happens at your destination, and now you need new orders. Your commander sends a message up the ranks, all the way to the great leader of the army. It takes 3 days to arrive. Your emperor, steak-in-mouth, takes great care in thinking through the order he’s about to give, and sends the messenger off, horse and all, on his way back to you. In the 6 days you’ve been waiting, a lot has changed, and the new order, while still executable, leads you to your doom. And now tell me this—is that not hilarious?

Let me interrupt your laughter (are you not laughing?) with one of my favorite passages:

“Houses are being set on fire in your presence and you stand still! What is the meaning of it? You will answer for it!” shouted Berg, who was now assistant to the head of the staff of the assistant of the chief officer of the staff of the commander of the left flank of the infantry of the first army, a very agreeable and prominent position, so Berg said."

Perhaps the most striking pages within War and Peace are those exploring the true meaning of power, where it lies, and how it comes about. If the feeble and isolated Napoleon (as he is referred to on occasion) were to give an order, what compels the millions of people under his “command” to carry out that order? Does power not lie, in reality, in the hands of the multitude, the ones with legs to move and weapons to shoot? Was he in command of his army, or was the army operating on its own, with Napoleon a mere symbol?

Is it not profoundly puzzling how the many continue to fulfill the maniacal desires of the few? When sanctioned by the state, mass murder and genocide are deemed heroic (or at least ‘necessary’) acts. On August 6, 1945 at 8:15 AM, pilots Paul Tibbets and Robert Lewis dropped the first nuclear bomb ever used in a war. Stop for a second, place yourself in that time and space, and think about what you might’ve been doing at 8:15 in the morning, seconds before you were turned to dust. Till the day they died, Paul and Robert maintained their belief that they were heroes, and that they did the right thing by wiping out 100,000 Hiroshima residents. After the war, and with great pride, they made money off the incinerated bodies of their victims, writing a book here, selling a manuscript there, and gleaming as they recounted their ‘adventure’ aboard that destructive warbird the Enola Gay. I am, of course, oversimplifying the matter, and nothing in the world is ever so simple. Before you point the following out to me, as I’m sure you are eager to: Yes, I know that those two bombs are tiny blips compared to other acts of genocide from recent history, some of which are still ongoing. Anyway—I will not pretend that I understand war, so I shall leave you to do with these thoughts what you will.

But first, this passage:

“At the end of the eighteenth century there were some two dozen men in Paris who began to talk all about men being equal and free. This led people all over France to fall to hewing and hacking at each other. These people killed the king and a great many more. At that time there was in France a man of genius—Napoleon. He conquered every one everywhere, that is, he killed a great many people, because he was a very great genius. And for some reason he went to kill the Africans; and killed them so well, and was so cunning and clever, that on returning to France he bade every one obey him. And they all did obey him. After being made Emperor he went to kill people in Italy, Austria, and Prussia. And there, too, he killed a great many."

I fear you may be losing patience with me, so now let me tell you about this book. Aside from the commentary on war and the patheticism (sue me) of emperors, the book talks about the lives of five elite Russian families in intimate, boring, long-winded detail. I hope you don’t misunderstand me—yes, it is a tedious read at times, but that’s a reasonable price to pay for a world so real, and characters so vivid that you could hear their hearts beating through the page. On regular days I don’t care much for drama, but in War and Peace I tolerated it, and even enjoyed it on occasion. In this moment, of course, I am grateful that the author is dead and cannot talk back, and I hope that his biggest fans will pardon me, a mere nobody, for my words.

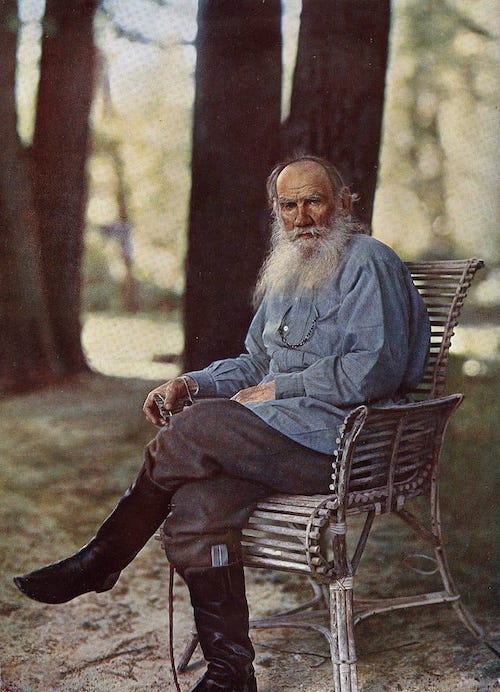

It’s worth noting that Tolstoy himself came from an aristocratic Russian family. His participation in the Crimean War lead to his conviction that governments are nothing but violent enterprises built to exploit their citizens. He also believed that the rich were a burden on the poor, and is said to have renounced his own wealth as a result. When, exactly, this happened, is unclear. What is evident is that War and Peace contains much of the author’s own life and philosophical beliefs, and in that light, it is not difficult to imagine how this gargantuan was birthed.

You may now be wondering about my dear one, mentioned earlier, who may or may not be fictional, and may or may not read this. I urge you to stop right there—the less you and I dwell on this subject, the better a chance there is for peace. Instead, distract yourself with the following tidbit:

“When a man finds himself in movement, he always invents a goal of that movement. In order to walk a thousand versts, a man must believe that there is some good beyond those thousand versts. He needs a vision of a promised land to have the strength to go on moving."

As we head, as a species and in conclusion, towards our inevitable doom, I would like you to think, for a moment, of the one book that you might wish to bring with you into your underground bunker when the maniacs of the world go nuclear and the climate collapses on our soft, squishy little heads. It may not be War and Peace, but at least if you read it, you wouldn’t have to wonder if you made the wrong choice, and we can all, hand in hand and shoulder to shoulder, scream “huzzah” before the end of times.

Hi there! 👋 Want to be informed of new posts via email?